Seashell Aesthetics:

Nature-Camp in the era of Expanded Identity and Shrinking Resources

Martabel Wasserman

“When I was little I held stones up to my crotch to feel the coldness, in order to move mountains you’ve got to know what stones are about.” – Mary Beth Edelson

“Energy moves in cycles, circles, spirals, vortexes, whirls, pulsation, waves and rhythms, rarely if ever in simple straight lines” - Starhawk

I work near the ocean, where dramatic cliffs overlook sunbathing seals and cargo ships in a single frame. Container cranes and the smell of oil refineries punctuate my commute. On lunch breaks, hoping to see whales, snails and everything in between, it is a knee-jerk reaction to look for embodiments and images of resistance and hope to barnacle myself to, as I wade in the tide pools next to one of the busiest ports in the world.This private ritual has led me to this public declaration: in these times, we need more seashell aesthetics.

Flower power yielded some important insights. It created an alternative to rigid gender- and class-based uniforms—a flamboyant rejection of compulsory conformism. Through figures like Allen Ginsberg, its optimistic approach to politics found grounding in the cynical observations unearthed by the Beatniks. Non-(re)productive pleasure and sociality were posited as valid responses to political turmoil with rallying cries such as “Make love, not war.” Flowers privilege the ephemeral; the quick arc from bud to blossom is part of their allure. Flower power emphasized the gathering or happening; it was a full embrace of the performative as transformative. Flower power promoted shape-shifting in wild colors and trippy shapes to accelerate the changing times. It was about be-ing; a radical presence.

However, in the age of Coachella-chic and Burning Man anarchism, the legacy of a flower power politics of pleasure is ticketed. Commodification of subversive aesthetics, (and thus the evacuation of their content) is probably inevitable under the current conditions of capitalism. We constantly need to re-fresh imagery. Given the constant process of hollowing out, why not start with a cavernous symbol?

Seashells represent deep time, and their longevity is partly responsible for the awe they inspire. Where flowers expand, rambling across space, shells contract, spiraling upwards into fierce beautiful points. As sea levels rise, we cannot think outwards but rather upwards, in spiral formations. The spiral formations of the shells do not use the dangerous logic of the pyramid, where the many support the few (although this shape has many powerful positive connotations as well), but rather they are structures in which the most gooey and precious-vulnerable parts of individuals are protected and honored. Seashells and their denizens also share communal habitats like beds and corals; snails, for example, share the shells they outgrow—they create structures to be reinhabited.

The seashell, one of the first fossils discovered, is always about a connection to the past. As our climate is in crisis, largely due to fossil fuel consumption, our relationship to deep time requires healing. The spiral contained within certain shells themselves is a reminder to queer the straight line of progress. If our understanding of progression is not queered, the ruthless depletion of finite resources and mortal bodies will march on.

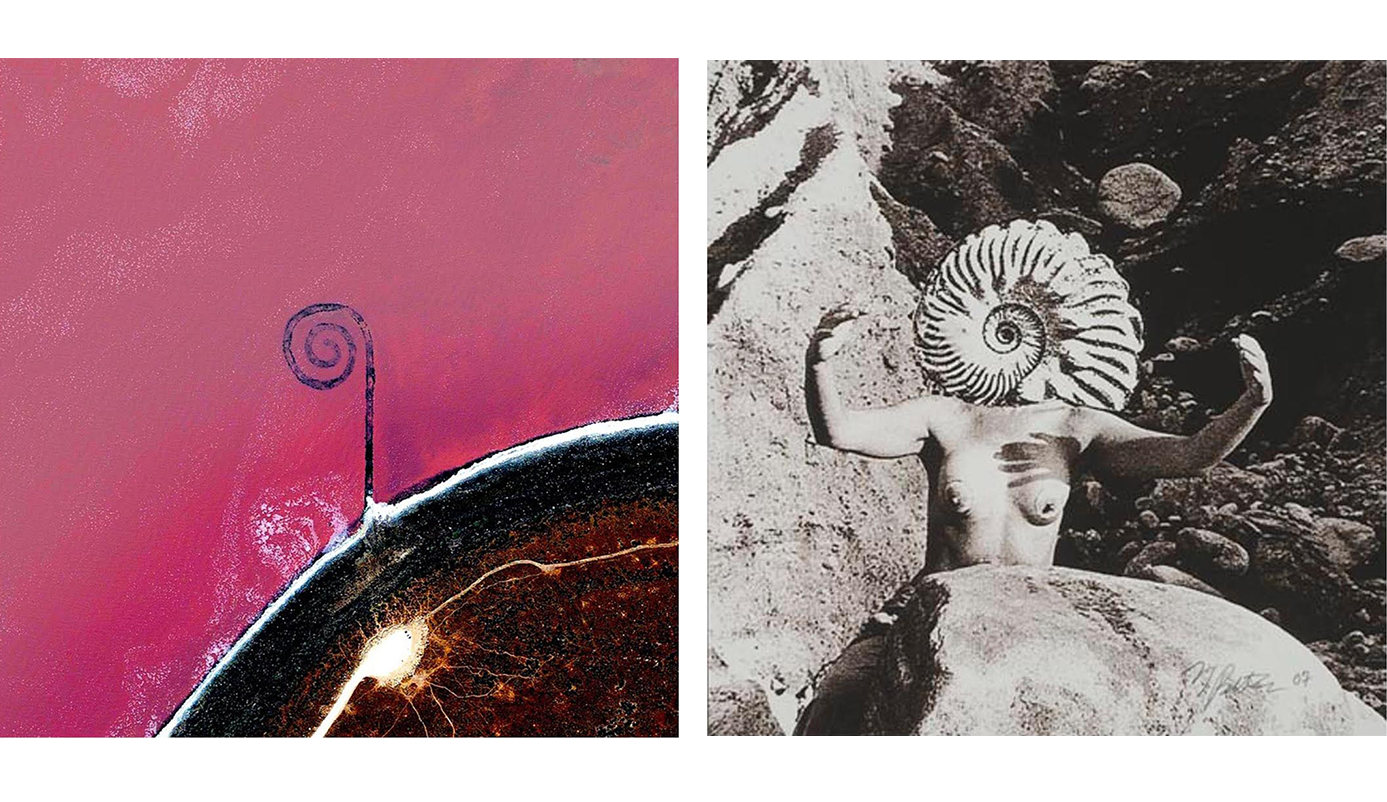

Image:

Seashell Aesthetics #1

Digital Collage by author

Dimensions variable

2016

Aesthetics are a spiral dance, constantly turning to face the past. What is a spiral dance? The spiral dance is a direct reference to Starhawk’s 1979 neopagan classic .The Spiral Dance: a Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. The dance itself consists of moving with linked arms in a snake-like movement that eventually leads to every participant facing every other participant. It requires making eye contact with your community as ritual. The individual's movement in and out of the spiral formation honors the cycle of life/death/rebirth, as well as the great neverending cosmic spiral. Connected to cultural feminism and an interest in women’s spirituality as distinct from the patriarchal top-down structure of major religions, the Goddess movement experienced great backlash with the concurrent but distinct emergence of both post-structuralism and neo-conservatism.

As Donna Haraway wrote in 1983, "Though both are bound in a spiral dance, I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess." Haraway is calling out Starhawk and other Goddess-worshipping feminists. Her critiques of the resurrection of the Goddess are directed toward the implications for identity politics, in which there is an essential connection of woman to nature and in which those terms go uninterrogated. Through looking at new possibilities of embodiment, Haraway rejects the return to nature and embraces the crafting of political subjects that use the garbage from which our subjectivies are already crafted. She posits the cyborg, an intersection of machine and animal that rejects any origin story of the natural.

The main trouble with cyborgs, of course, is that they are the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism. But illegitimate offspring are often exceedingly unfaithful to their origins. Their fathers, after all, are inessential.1

If we are willing to see the cyborg and goddess as bound in a spiral dance, though, we can look to the past without an investment in an origin. Through this spiral movement, we can unearth ideas from the Goddess revival moment that do not negate or privilege any particular genders or ideas of the natural.

Let’s first turn to two examples of the spiral in the art of the 1970s for insight into how the Goddess and cyborg can face each other.

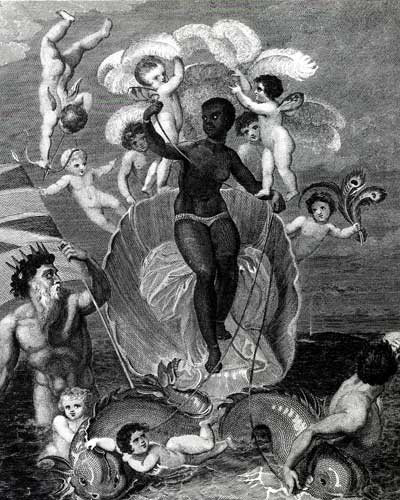

In 1975, feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson did a series of photographs exploring her relationship to Goddess imagery. The body of work consisted of her doing private nude rituals in outdoor settings. She altered the photographs with various painting and collage techniques in order to layer history on top of her body and create a hybrid form, before Photoshop and the advent of the avatar. Edelson was deeply involved in the Goddess resurgence movement; she was a member of the NYC-based "Goddess Group" with comrades like Merlin Stone, as well as a co-editor of "The Great Goddess Issue" of the feminist journal <span class="italics"Heresies</span> in 1978.

Edelson defines the Goddess as follows:

SHE is, for me, an internalized sacred metaphor for an expanded and generous wisdom that respects all peoples. SHE is alive and evolving in contemporary psyches as well as being an ancient, primal, creative energy in both women and men that embodies the balance of intellect-body-spirit. SHE sees clearly unacknowledged radical truths in accepting both the dark and light sides of the way it is and yet SHE does not forget to be playful. Dogma is an anathema to HER. HER presence is inconstant when SHE is scorned, but when embraced SHE manifests in dynamic, nonhierarchical networks of cooperative relationships that include actively working for human liberation.2

Being so involved in the turn towards women’s spirituality and the feminist art scene of New York in the 1970s, Edelson was also at the forefront of the response to the backlash against cultural feminism in the 1980s. She writes of this backlash against feminism as both alienating the individual from the community and the feminist artist from an intuitive art practice. To generalize this context of the art-world with some big names: there were the individual gestures of Edelson, Ana Mendieta and Hannah Wilke creating their own embodiments of the Goddess, as well as the land art projects of Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria and Michael Heizer attempting to alter the landscape on a massive scale.

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) took "292 truck hours, 625 man hours […] to move 6,650 tons of earth".3 The different processes of Edelson and Smithson can be read through the historical (and contemporary) challenges of making feminist art; in other words scale can correlate to access. This not always the case, and the small gesture has proven to be powerful by many feminist artists. I am complicating binaries here, but nevertheless, I want to call out the material realities. Both works, though, have surprisingly similar ideas about myth and earth. Edelson’s work insists upon the importance of earth-based beliefs as a way to heal the effects of patriarchy on the land and spirit. Smithson is interested in reclaiming earth that has been exploited, arguably by patriarchally-informed ideas that cast earth as a resource rather than a source—the site of the Jetty was previously used to mine oil, and the shape itself references a mythological whirlpool at the center of the lake. The operation in both works is one of reclaiming: Edelson’s ideology to Smithson’s landscape. The connections between these two very different works also extend to the deconstruction of the studio art practice that was well underway in the 70s. The Goddess and the cyborg both called the maker out of the cube and into larger landscapes. The useful legacies of these distinct approaches to reclaiming a relationship to the earth must also be read through a pitfall of environmentalism where we are left with the options of individual and/or grand gesture as a tactic. They push us to ask how to engage the collective in a path towards systemic change. Let’s work with the equation: Edelson is to Starhawk what Smithson is to Haraway. What is dialectic if not a spiral, a making eye contact with your inverse?

There is the earnest individual relationship to nature as a sacred Goddess dance on one hand, and the cynical-yet-optimistic cyborg jig on the other. Imagine a rock in your pocket and a protest sign raised at a site where power goes unchecked. Think of the conch shell filled with sage at the #NODAPL rally being shared over Instagram—the individual and collective moving together. The Cyborg allows us to see gender and the body as technologies, in its own way empowering newly primal paths toward connecting with the wild. The Goddess has been showing up in culture in new ways that allow her to move away from gender, with phrases like "The Sacred Feminine" appearing on a dream sequence on Transparent. In this instance, we see the Goddess throughout the series promoting a feminist politics centered on experiences of oppression but untethered from biological sex. With stakes very distinct from those in popular culture, we see protection for the Earth as Mother and women on the frontlines of a coalition to resist colonial and capitalist destruction of land in #NODAPL. Simultaneous to making space for these gendered representations, the coalitional nature of the movement challenges simplistic notions of both indigeneity and gender as sloppy shorthand for planetary empathy. The individual and the collective are bound in a spiral dance, as are the goddess and the cyborg. They are being woven together by new formations of resistance, which honor individual connections to the sacred and use the tools of late capitalism—such as the web itself—in order to resist it.

1Haraway, Donna. "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late 20th Century." The International Handbook of Virtual Learning Environments, 1985: 117-58.

2Edelson, Mary Beth. "Success Has 1,000 Mothers." Women’s Culture In a New Era: A Feminist Revolution, ed. Gayle Kimball, Scarecrow Press, 2005

3Kastner, Jeffrey, and Brian Wallis. Land and Environmental Art. London: Phaidon, 1998. Print.

Images:

Goddess Head

Mary Beth Edelson

Photograph and collage

Dimensions variable

1975

Spiral Jetty

Robert Smithson

Basalt rock, salt crystal, earth, water

15 feet x 1500 feet

1970

Throughout antiquity, scallops and other hinged shells have symbolized the feminine principle. Outwardly, the shell can symbolize the protective and nurturing principle, and inwardly, the "life-force slumbering within the Earth" an emblem of the vulva. -Wikipedia

Similarly iconic to the Mona Lisa, Botticelli's rendering of the Goddess of Love in The Birth of Venus makes her particularly ripe for parody and reference. Mona is to "Art" what Venus is "femininity." With some distance from 1970s cultural feminism, there is now a return to Goddess imagery. With this cultural trend, there is an opportunity to reconsider the politics of Venus within our current climate. This is a jaunt through some of her more recent appearances and predecessors, with an eye from the middle of the last century through the present. We move from a spiral formation, to a scalloped half looking for its mirror image. These images sheds rays of golden Goddess light onto how identity categories have expanded. How do these expanded notions of identity relate to how we visualize the embodiment of love?

Warhol’s take on Botticelli offers a starting point for this abbreviated investigation into her contemporary likeness. When Warhol gave Venus his treatment, he removed her from the sea to serve us face, face, face. She is disconnected not only from her body and from the larger body from which she was birthed. Pop Venus reinscribes a nature/culture dichotomy, her connection is not to the earth but a reproduction of a reimagining. On a (very) surface level, he makes another intervention into Venus as pop-star portrait. In a version that appears like a solarized photograph, we see Venus as black. Unusual for Warhol, but not for feminists of color and others seeking to decolonize/reclaim images of power.

The challenge of representing extraordinary Goddess power and the horrid ordinariness of violence is taken up in Alison Saar’s "Strange Fruit" (1995). The figure, with the same hand gestures as Venus rising from the shell, is (as the title references) suspended as a lynched figure. Saar’s is not about emergence of an archetypal love force from a natural body, but an individual murdered by a matrix of economics and culture that birthed a nation. Robin Coste Lewis recently re-claimed the image "The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies," an eighteenth century engraving by Thomas Stothard, which depicts the Middle Passage. Her collection of poetry Voyage of The Sable Venus is a catalog of the black female body in art history, using poetry as a rebirthing process.

Moving from Warhol to Saar, to Stothard and Lewis, back to Warholian genealogy is jarring despite the ways in which our screens teach us to look at cuteness and violence in a scroll dance. Bodies are rendered as commodities in extremely different ways. The aesthetics of the shell offer a moment to contemplate the life that is no longer there. Looking at interpretations of Venus in this light, with an emphasis on her emergence on the half shell of another creature no longer alive, can be pregnant with pause. A fertile moment we need in order to take “Strange Fruit” and Lady Gaga as distinct threads in a complex tapestry. Please, Venus, grant us this moment of contemplation upon your shore.

Lady Gaga, a self-identified descendant of Warhol, gives us her interpretation of Venus in a video for the song of the same name. The video moves between a Warhol-esque room of silver balloons to shots of Gaga in an empty space donning a wig cap and holding an assortment of locks while making out with a genderless Styrofoam head. She has paid homage to Venus in other videos, such as "Artpop" in her seashell bikini. Gaga’s reccurring Venus trope bears similarities to work by the performance artist Narcissister. As Gaga seduces the doll, Narcissister becomes it. Both artists work in the performative space where the cis-female and drag queen overlap. This recognition of femaleness as performance, as parody, in which Gaga and Narcissister play, was viewed as blasphemous in certain sects of second wave feminism.

The constructedness of gender was being exposed at the same time as many feminists gathered around an earnest desire to reclaim a connection of woman as earth. Not only did this line of thinking prevent coalition with gay comrades, but it also short-circuited opportunities for playing with gender roles, even shaming those who did not conform to traditional (feminine) gender presentations and who enjoyed sex acts involving strap-ons. A Venus intervention by Joel-Peter Witkin in 1988 allows us to see a trans Venus in her full feminine glory, penis and all. While Witkin’s work can easily be criticized as employing the straight male gaze, there are other examples of feminist and queer photographers finding important contributions in the images he brought forth. Third-wavers, queer theorists, and trans activists have created more space within feminist thinking to play with performance, such as Gaga, who is able to reference in her self-consciously performative interpretation of the Goddess of Love. As well, in her piece “Changes” (a reference to a non-binary saint of the glam variety), Narcissister undergoes a series of character transformations. Layered with wardrobe changes and mask reveals, she goes from witchy monsters to doll faces in peach and brown tones, until her ultimate reveal as Venus on a shell. While the birth-as-Venus seems to be the great reveal, she then takes it one step further by putting on a solid white latex mask, becoming a pearl. As a pearl, she moves from gendered body to gendered symbol. The pearl is a stand in for a nexus of pleasure and/or self-salved wound.

Alain Jacquet picked up another aspect of Venus more likely to be taken up by cultural jammers than pop stars. In his 1964 "Camouflage Botticelli (Birth of Venus)", Venus is rendered as gas pump. Her face is partially covered by a transparent Shell logo. The text “Shell” hovers adjacent to her breasts and over her genitals, advertising her sex as commodity and for profit. Rendered in the horrid hues of yellow and red that evoke the ketchup/mustard combo of McDonald's, as well as numerous other logos from In-and-Out Burger to Doritos, the Shell logo tries to make itself irresistibly delicious. Jacquet’s Venus allows us to see the Goddess as Pop Princess plastered in logos. You can almost hear a Disney Princess laugh, like she is both in on the joke and knows it’s not funny. Also in 1964, feminist artist Barbara T. Smith created an image using the Shell logo, complete with bloody brush strokes, which resurfaced in a 2016 exhibition in Los Angeles. Apparently Venus was speaking up about the exploitation of fossil fuels loudly that year, hitching a ride on the Pop wave.

When the oil giant Shell was leaving Seattle with the "Death Star" for offshore drilling in 2015, activists and other protesters on the ground in solidarity also used the Shell logo with the phrase "Shell No." Still others made the logo look like a hand giving a middle finger, using graphic play to express rage at Shell's plans for further drilling of the coast of Alaska. Another anti-big-oil image shows a bird covered in oil rising in the place of the Venus. Whether she's a bird or a mermaid resembling Disney’s Ariel drowning in oil, in all these images, the Goddess is rising as already dead.

When we can picture Venus as having a penis, or as a nonhuman creature such as a bird, there is new space within seashell aesthetics to see birthing and embodying love as detached from biological sex. When the clam is returned, in its vulvic glory, as a visual, where the adjoining shells each represent a side of the nature/culture binary, there is no need to pry it apart for a single seed origin. Let us look at two halves together.

4This partially draws on the accounts of drag in Noretta Koertge’s Valley of the Amazons (1984) and other second-wave literature

5Samaras, Connie, "Feminism, Photography, Censorship, and Sexually Transgressive Imagery: The Work of Robert Mapplethorpe, Joel-Peter Witkin, Jacqueline Livingston, Sally Mann, and Catherine Opie," New York Law Review, 1993

Images:

Birth of Venus 318

Andy Warhol

Screenprint

32 x 44 inches

1984

Strange Fruit

Alison Saar

Sculpture

1995

The Voyage of Sable Venus, from Angola to the West Indies

Thomas Stothard

Etching

c. 1800

Applause

Lady Gaga

Video Music Awards performance

2013

Changes

Narcisister

Performance at the Spectrum, New York

Screen shot of documentation

2013

Camouflage Botticelli (Birth of Venus)

Alain Jacquet

Oil on canvas

1963-64

A sailor’s valentine is an elaborate shallow box embedded with designs made out of seashells. It is beautiful to think of the process of collecting, sorting and carefully laying out shells in heart and flower shapes as a way to process feelings of longing and distance. These sentimental objects, most popular in the mid- to late- 1800s, can be traced back to shops owned by British brothers on the colonized island of Barbados. Not only were local women making these objects to be sold by British men, but shells were also imported from Indonesia to create them.Global capital sours sweet nostalgia.

Abalone shells, popular amongst witchy femmes as dishes for smudging sage, are currently endangered. The iridescent shells are often used in jewelry, beautiful nature psychedelia that signifies a connection to the earth when worn. It is only upon further research that we discover the mollusk that produces the purples, blues, pearly whites, greens and pinks reveals itself to be precarious. The endangered creature as hippy accessory.

Like flower power and everything else from riot grrrl styles to hacktivist hoody-chic, the aesthetics of Camp have been commodified and diluted. Dragged through the cultural ringer, where live-for-TV musicals pump saccharine into the gritty goodness of classics like Hairspray and Rocky Horror Picture Show. The shell, most often depicted as a hollow vessel rather than as a protection for gooey bottom feeders, is evacuated and ready for rehabilitation. Camp offers a similar Trojan horse, a space to re-enter. And given the dire need to address climate change in a systematic way, the shell is a powerful reminder that we must honor and not expropriate the remains of life. It is a call to honor the dead in a new way. Camping nature, or “Nature Camp,” offers a way to bridge these tendencies in our moment of climate crisis.

Bold claim: seashells allow for connections between historically contentious tendencies in queer aesthetics—cultural feminist imagery and Camp (as they emerged in second-wave feminisms and concurrent strands of gay liberation). In crudely generalized terms, womyn's liberation turned to nature and gay (male) liberation looked to culture in order to subvert or coopt politically resonant images. Activist warriors across the gender spectrum have hacked away mightily at the categories that created these initial divides (female/male, nature/culture, core imagery/camp), so much that it might seem silly to even look back. But again, this is a spiral dance. In this iteration of our turn, the shell both stands for a deep connection to nature with the baggage and beauty of "feminine" imagery it hauls with it, AND links to the Camp strategy of crafting detritus into monuments to survival.

Camp crafts from crap. Both the crap of lived experience as the other, and the material crap of capitalist culture. Camp heals, Camp sustains, Camp gives life. But as Sontag wrote in 1964, “Nothing in nature can be campy.” This makes sense historically. The homosexual as an identity emerged as an unnatural diagnosis. Embracing artifice and the constructed is central to this legacy. The unnatural, or deep criticism of the natural as itself a culturally-constructed category able to be employed for hegemonic purposes, remains useful as the cyborg and others have shown us. Gay liberation, like feminism, has a history and theory full of contradictions. The Radical Faeries and Cockettes, for example, incorporated nature into their Camp. Seashell crafts, mermaid drag, and queer beach communities all connect the imagery of the seashell to Camp strategies. These examples of Camping nature, or "Nature Camp" allow for connections with other strands of queer feminist aesthetics, which Sontag did not leave space for in her "against nature" definition.

The seashell, with its vulvic hues of pink, purple and brown, is open to connecting with histories of feminist imagery. Feminism(s) took many different approaches to the idea of women’s relationship to nature during the crest of the second wave. Some lavender menaces used guerilla tactics to get a seat at the table. Others said screw the table, let's go back to the land and gather around a campfire of our own. But as the canon tends to do, it centered a particular aesthetic as the dominant one of this historical moment, in this case core (aka vulvic) imagery. Examples of this core imagery, perhaps most famously Judy Chicago’s "The Dinner Party" demonstrate the problematic nature of reducing woman to genital imagery, which I won't rehearse again here. Instead, I want to praise the power of the quotation marks Sontag bestowed upon us with her definition of Camp in which a lamp is not a lamp but a "lamp." Using this logic, we can view vaginal imagery as "vaginal imagery." Feminist renderings and musings from Chicago to Mary Daly can be revisited with critics in tow. Camp grants us permission to dabble in the problematic and the overly simple. Irony here does not eclipse sincerity, rather it makes visible the narrow confines in which sincerity seeks to take up space. Thank you seashell, for guiding me to these musings.

Image:

Gay Beach

Digital Collage by author

Dimensions variable

2016

Thinking with the seashell, pressed to my ear or held against my chest, has ultimately led me to name a performative strategy in play not yet clearly defined. I am calling it "Nature Camp." The ways in which Camp has reframed culture and posed critical questions about taste as ideology can and must be applied to how we look at what we call "nature." Looking at nature as constructed itself, with Camp as a strategy, helps dislodge the residue of ideas of innate connections to the planet bound up in ideas of gendered spirituality. We can revisit what was previously discarded, such as legacies from neo-pagan art, Goddess-worshipping feminism, and Camp itself, after all it’s been through.

Nature Camp is a strategy long in play. Radical Faeries mixing glitter and dirt. Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens spreading the doctrine of ecosexuality. Masturbating with a crystal in AK Burn and AL Steiner’s Community Action Center. Its Bread and Puppet style giant Octopus performing at the "Sunken Cities" exhibition sponsored by BP at the British Museum complete with mermaid’s protestors of all genders arguing climate change would be good for their underwater real estate interests. I saw it when I witnessed JD Samson fist fuck a bag of topsoil as part of a durational performance in Ba Na Na’s collaborative Elements Project. I saw it when Edgar Fabian Frías used electronic music to cast spells against Nestlé’s hideous water theft. I saw it when I read Sam Cohen's queer and imaginary re-historicizations of real animals as part of her work as The Institute for Flying. I saw it when Sea Shell became the alter-ego of Michelle Antonisse. These examples and others honor a sensual connection to the earth while also layering on artifice and humor that pull you. Spectacle and soil, a queer combination indeed.

Nature Camp is in no way bound to seashell aesthetics, although contemplating the shell and representations of it gives us some provisional notes to go on.

Seashells teach us about ornamentation as protection.

Seashells motifs are analogous to skulls and crossbones. They can help us rethink an aesthetics of death, which is in much need as we continue to pump the past into our fuel tanks with reckless abandon.

Seashells give us a mermaid imaginary, a queer animal- human hybrid that allows us to play with new ideas of embodiment. Mermaids give us non-genital sexual fantasies. They give us great drag and amazing tchotchkes, gifts of camp’s legacy. Visual pleasure in all sorts of detritus.

Seashells give us vulvic imagery detached from the sex of the creature. They allow us to play with core imagery not centered on gender.

Seashells are power bottoms. We can rejoice in the generative nature of the bottom feeder, and find queer pride in the ways in which their faces and genitals are seemingly indistinguishable.

Seashells bring us back to the spiral. They allow us to circle back critically, and experience duality, dichotomy, and dialectics less like a ping-pong ball and more like a serpent

Nature Camp can and must be applied to subjects such as the cactus, the seed pod, fungi, boulders, geodes, and the like as we seek to reorient how we relate to our environments. Nature Camp and Seashell Aesthetics are a call to the site-specific, a way to sort through the layered history of place through touch and theory. It's a queer wave. Riding stormy seas, a vessel both empty and full.

Images, all collaged by author:

Photograph of shellfish, source unknown

All Natural

Ba Na Na

Performance Still

2016

Shell witch, source unknown

Give Us Goddess Womb

Edgar Fabian Frias

Performance promotional image

2016

Community Action Center

A.K. Burns, A.L. Steiner

DV video (Still)

01:09:00

2010

Photograph of shellfish, source unknown

Oxford Blue Wedding

Annie Sprinkle + Beth Stephens

Performance Still

2009

T-shirt, source unknown

Sea Shell at

Michelle Antonisse

Performance Still

2016

Protest at "Sunken Cities" Exhibition

BP or Not BP

British Museum</br>

2016

Martabel Wasserman is a writer, artist, curator and Sagittarius living in Los Angeles with her two chihuahuas and femme lover. She has written about fierce pussy, the AIDS crisis and the aesthetics of solidarity. Curatorial projects include Fire in Her Belly, Hold Up and Coastal/Border (forthcoming). She was the founding editor of RECAPSmagazine from 2012-2014. She has shown photography in Providence, NYC, and LA and is currently getting back into her studio practice after a hiatus post graduate school. She also identifies as a femme.