On Mysteria: H.D.'s mystical, hysterical poetics

Meaning to write the word “Mysticism” and then the word “Hysteria,” my hand instead scribbled “Mysteria” in my notebook. Perhaps this is a good way to begin. In H.D.’s work, the poem’s way of knowing is mysterical. This is not the ascetic mysticism so often associated with male spiritual heroes, but an embodied and excessively emotional connection between the self and the divine. The mystical experience is a trembling open of a small psyche into a sea-green vastness. It is a profound though temporary conversion from mundane reality to the world of spirit, myth, and dream. Like unbearable pain, the mystical experience also ruptures language, space, and time. In the wake of this dissolve, new images are offered. They rise up from depths or descend into a body from above.

H.D.’s mysteria begins in her body and therefore in her own biography. In Notes on Thought and Vision, she writes: “the body... like a lump of coal, fulfills its highest function when it is being consumed. When coal burns it gives off heat. The body consumed with love gives off heat... Perhaps so we cannot have spirit without body, the body of nature, or the body of individual men and women” (48 - 49). This mysteria is heresy. The spiritual reality H.D. accesses in her visions is not part of any religion or even an occult sect— it is entirely her own. H.D.’s mysteria is also heretical towards the violent, capitalist patriarchy she was born into and suffered under during both world wars. In some ways, her visions and poetry are also heretical to male modernist literary traditions. H.D. left behind her early fame as one of Ezra Pound’s Imagists in order to invent her own poetics, where writing became a site of contact between spiritual and material planes. Though H.D.’s use of poetic images is rooted in Pound’s concepts, it was her lifetime work to develop a more visionary potential for what an Image signifies. This work is inseparable from H.D.’s actual visions— her mystical or paranormal experiences. It is in her accounts of these events that H.D. is at her most mysterical. H.D.’s visions not only empowered her to survive decades of trauma but also forged the invisible architecture of her poetics.

Robert Duncan, queer mystic in a foggy cape, kneeling at the feet of H.D.’s tomes, writes in The H.D. Book: “to be a poet is to be reborn— to be baptized, initiated, graduated, analyzed” (69). Duncan was one of H.D.’s greatest champions, working to reclaim a place for her in the canon from which she had been excluded. He describes how he first heard H.D.’s poem “Heat” read aloud to him in his high school classroom and felt an epiphany so powerful that it converted him to a life of poetry. Duncan’s devotion to H.D. is that of an initiate to a master. Through H.D.’s writing and biography, Duncan found an alternative to patriarchal systems of authority and notions of how one must live. Duncan, like H.D., believed that the poet dwells in a “romance that must create its own terms of existence in the midst of realms of empire and commerce that seem to most men patently realistic” (72). H.D.’s mysterical poetics served as a model for how a sensitive, creative spirit like Duncan might survive in a world made incoherent by violence.

Reclaiming H.D. from the shadows of modernist anthologies, Duncan’s The H.D. Book bears witness to a woman in the shadows of men, to mysticism in the shadows of religion, to poetry in the shadows of the world’s dangerous prose. Duncan himself was enshadowed by H.D. and her mysteria. He wore her shadow like a doctor of philosophy dons a velvet gown and marches down a lane of careful grass. He wore her shadow like a shield against the sufferings of daylight.

The mysterical poet serves the poem like a priestess serves an altar. The poem is an Image of spiritual reality. What I mean by Image here is something like Ezra Pound’s 1913 definition, where he wrote that Image, with a capital-I, is: “that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time.” The Image gives readers “the sense of sudden liberation; that sense of freedom from time limits and space limits; that sense of sudden growth.” So a poem is not only made of images, it is itself an Image, by which I mean a site of revelation: a place of contact between the embodied experience of a reader and a disembodied, timeless realm. A mysterical poem is a portal for entering a spiritual reality that had been previously hidden or inaccessible. A door into another person’s dream. A spell that temporarily enchants. The mysterical poet has access to this other-realm because she has transferred her allegiance from kings, popes, and presidents. Her power also comes from feeling— perhaps too much of it. Writing, and the intense emotion that motors it, becomes the mysterical poet’s sacrament.

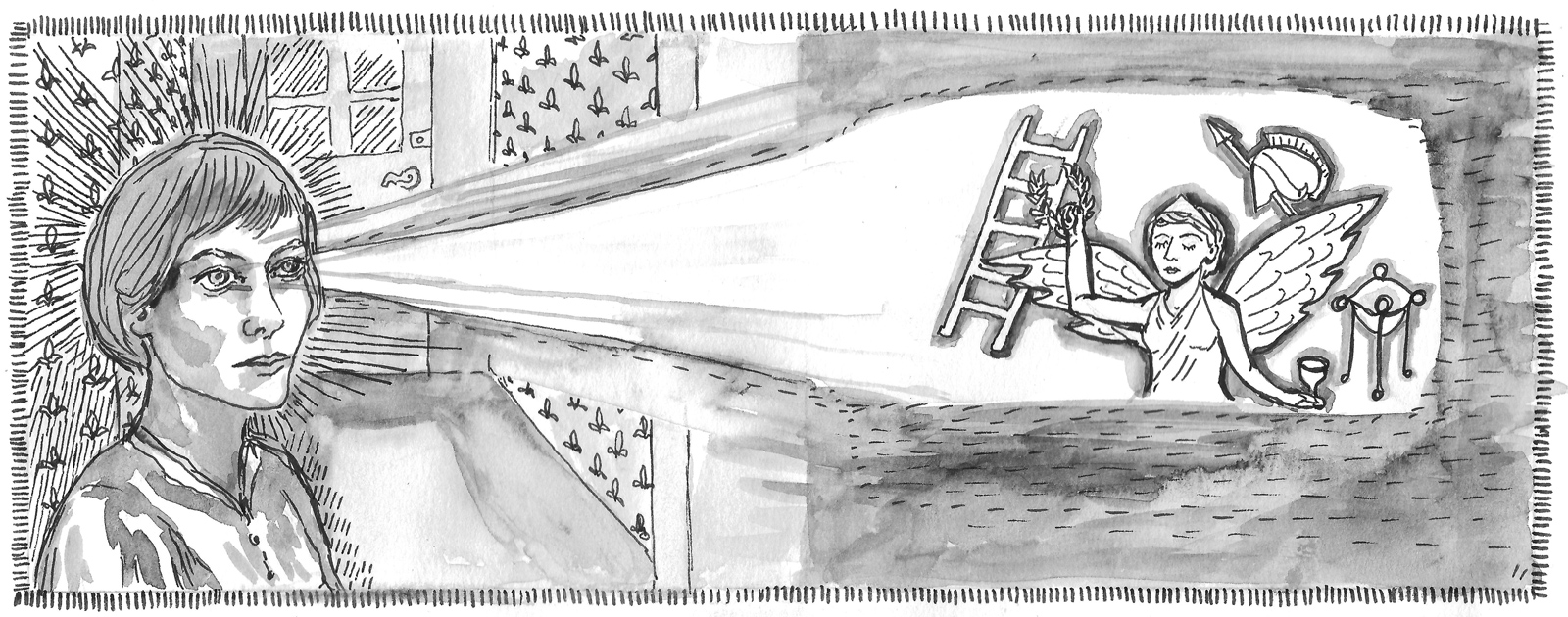

What would it be to feel something so strongly— pleasure or pain— that the feelings become bigger than one’s body? What do we call feeling when it exceeds self, exceeds the earth, exceeds the present tense? One of the central event’s of H.D.’s life was a vision she experienced in Corfu, Greece in 1920 which she called the “writing-on-the-wall.” H.D. said she saw the real apparition of images drawn in light on the wall of her hotel room. The pictures came in sequence: dots and lines coalescing into depictions of a soldier’s head, a chalice, a sacred tripod, a ladder, and the Greek goddess Nike, who symbolizes victory. H.D. saw these forms appearing through her intense concentration but also without her volition, as if she were a projector shining forth an otherworldly film.

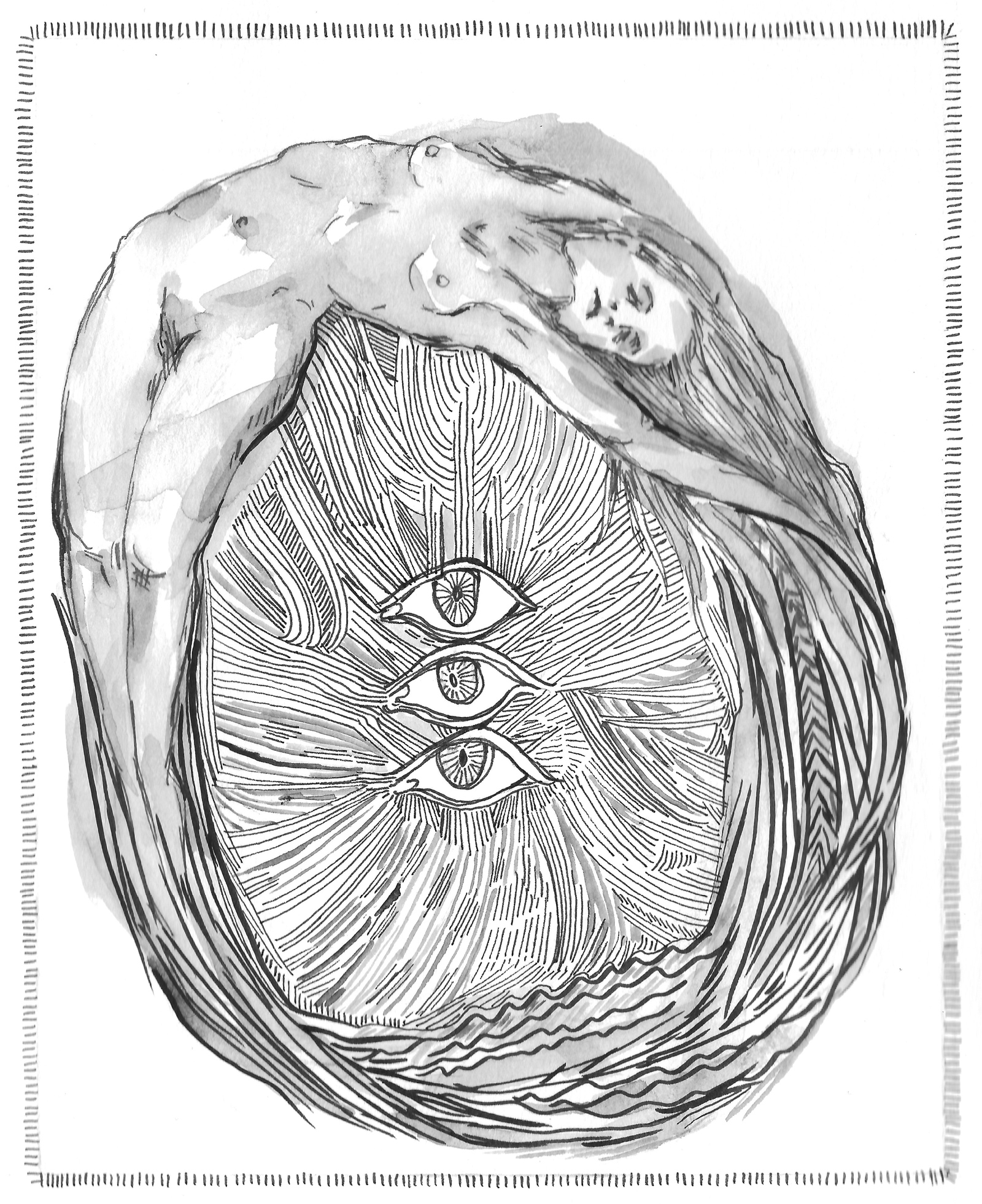

The wall vision came to H.D. after a period of intense crisis. Amidst the collective trauma of World War I, H.D. also suffered a stillbirth, a divorce, the death of her brother, the loss of several important friendships, and a second pregnancy which she and her daughter narrowly survived. By 1919, the year before H.D. would see the writing-on-the-wall, she felt physically and psychically destroyed— saved only by the benevolent intervention of a woman named Bryher, who became H.D.’s partner and patron. In July of 1919, H.D. began to have mystical experiences that she described as feeling like having a second mind, an “over-mind,” whose intelligence seemed to come from both a higher source and from her womb. H.D. describes it like this: “it seems to me that a cap is over my head, my forehead, affecting a little my eyes. Sometimes when I am in that state of consciousness, things about me appear slightly blurred as if seen under water” (13). H.D. wrote that it felt as if a jellyfish covered her head and reached its long tentacles down through the rest of her. She tells us, “I first realised this state of consciousness in my head. I visualise it just as well, now, centered in the love-region of my body or placed like a foetus in the body” (19). This second mind, located in the poet’s uterovaginal plexus, is the seat of mysteria. Not only did H.D. register individual and collective trauma through her body, she also experienced mystical states at the level of her physical self. It is as if the incoherence of trauma created a split between H.D.’s suffering body and her spiritual one— a positive and healing dissociation. This sense of floating up above intense pain is echoed in the aesthetics of H.D.’s poetry, which is austere, vatic, crystalline. Although the quality of H.D’s verse is not hysterical, her writing is the outgrowth of excessive pain transformed through mystical experience.

Treatments of female hysteria were aimed at curing a condition of the womb. The ancient Greek concept of hysteria, which forms the etymology of the word, is based on the idea that the womb of a hysterical woman wanders restlessly through her body. The womb resists staying in its designated place. Later, in 19th and early 20th century America and Europe, male doctors sought to treat hysterical patients with forced masturbation and psychoanalysis meant to uncover supposed sexual neuroses. In their analysis together years later, Freud called H.D.’s writing-on- the-wall vision her most “dangerous” symptom. In H.D.’s memoir of her time with Freud, Tribute to Freud, she suggests that the doctor did not share her sense that her vision was a prophetic message. In doubt over her own interpretation, H.D. writes:

We can read my writing, the fact that there was writing, in two ways or in more than two ways. We can read or translate it as a suppressed desire for forbidden ‘signs and wonders,’ breaking bounds, a suppressed desire to be a Prophetess, to be important anyway, megalomania they call it— a hidden desire to ‘found a new religion’... Or this writing-on-the-wall is merely an extension of the artist’s mind, a picture or an illustrated poem, taken out of the actual dream or daydream content and projected from within (though apparently from outside), really a high-powered idea, simply over-stressed, over-thought, you might say, an echo of an idea, a reflection of a reflection, a ‘freak’ thought that got out of hand, gone too far, a ‘dangerous symptom.’ (51)

The writing-on-the-wall was an Image the way a poem is an Image— “an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time.” As a poet, I am inclined to think H.D.’s vision was real; it was a real projection she and Bryher witnessed one afternoon in Corfu. In other words, the vision was real because it was emotionally true. The images H.D. saw were symbols reaching out from a traumatized unconscious to reassure and warn her that more trauma would soon come. The vision was not simply hysterical— not psychopathic. It was personal, produced by her own body, yet it also spoke beyond her. Like a prophecy, H.D.’s mysterical vision carried a crucial message meant for her entire community. What she experienced through her own psyche was translated for others into poems. More than twenty years after the writing-on-the-wall in Corfu, H.D. would write her most powerful visionary work, Trilogy, amidst the world-shattering explosions of the London blitz. It is the gift or perhaps the miracle of mysteria that what Freud thought of as H.D.’s most dangerous symptom was actually her cure. H.D.’s writing-on-the-wall was the psychic medicine needed to ensure her survival and to restore the artist to her art.

Works Cited

H.D. Notes on Thought and Vision. City Lights, 1982.

____. Tribute to Freud. New Directions, 1984.

Duncan, Robert. The H.D. Book. University of California Press, 2011.

“H.D.” Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/h-d.

Accessed 2 May 2017.

Pound, Ezra. “A Few Don’ts by an Imagist.” Poetry, March 1913, pp. 200 - 206,

www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/detail/58900. Accessed 2 May 2017.

Claire Cronin is a poet, songwriter, and doctoral student in Athens, GA. Her chapbook, *A Spirit is a Mood Without a Body*, won the 2017 Dead Lake Chapbook contest. Claire's work can be found in *Bennington Review, Sixth Finch, Vinyl Poetry, BOAAT, Cloud Rodeo, Yalobusha Review, The Volta*, and other journals. She has an MFA from the University of California, Irvine.