Too Much Emotional Trauma with my K-pop

There is a Korean rap competition show called Show Me the Money that I watch religiously. Tiger JK, one of the producer-judges on the most recent season, is considered the “godfather of Korean rap.” He is Korean-American and has stated that he began rapping as a way to ease tensions between Blacks and Koreans in the wake of the LA Riots. (He grew up in Los Angeles from age 12 and moved back to Korea after graduating from UCLA). I discovered this last year, during the 25th anniversary of the Riots. This, to me, seems like a tidy, humanist band-aid on a complicated and layered relationship.

Last year was the 25th anniversary of the LA uprisings and as a recent Los Angeles transplant I’ve been ruminating on the uprisings with new context and regional specificity. Although my mom took me to Rodney King protests in Brooklyn as a toddler, my knowledge of the specific events that led up to his shooting were general at best. Furthermore, I didn’t know about Latasha Harlins, a young Black girl who was shot in the back of the head by a Korean shop owner in LA before King was beaten, until I moved here in 2014. As a Black woman who believes that anti-Blackness lives everywhere, my recent fascination with Korean pop culture is leaving me with a really troublesome bout of cognitive dissonance.

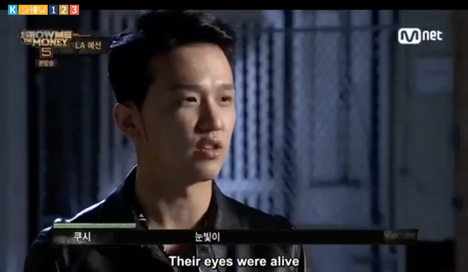

Every time I watch SMTM, I steel myself for either egregious appropriation or, at the very least, the looming specter of unacknowledged Blackness. For example, last season during season 5, the show, for the first time, held auditions in the United States. Because of the large resident Korean diaspora, the auditions were held here in Los Angeles, with Timbaland serving as guest producer-judge. At the start of the show, there was a montage introducing the non-Korean rappers, who were mostly Black. Later in the episode, these Black auditionees are referred to as “Hip Hop’s Natives.”

I have mixed feelings. On the one hand, I believe that people should never forget that hip-hop is Black music. Its origins, like all of our music, lie in a dual expression of struggle and joy. But the loaded nature of the word “native” in reference to Black people in a cultural ecosystem that allows Blackface on mainstream television and understands itself as racially homogenous is a problem. Kush, one of the producers, says about the Black contestants: “their eyes were alive.”

The thing is, though, I’ve watched that season of SMTM twice (and went to the show’s concert in LA). I’ve watched season 4 through three times. Season 6 is currently airing and I’m such a fangirl I’ll watch the unsubtitled videos as soon as they drop and then rewatch the subtitled episode when it is uploaded. It’s actually taking all of my self-control to not watch the unsubtitled episode that just dropped right now.

But the truth is, the level of cognitive dissonance that I’m navigating isn’t the result of fangirling one Korean rap show. Right now, all I watch are Korean variety shows. I got my Master’s degree in Cinema and Media Studies, and I’m deeply concerned with how media circulates. I’m also a cinephile and have historically been a lover of television. My current this-is-too-much fannish tendency is a confusing departure from what I feel like I should be consuming. I feel guilty that I’m not watching a Black queer webseries or a Euzhan Palcy film or a Ceddo Film Collective documentary.

The weekend of October 4, 2015 was a terrible one for me. I didn’t know where my younger sister was and my mom and I were deeply worried about her. Simultaneously, a five-year best friendship had ended. I was too stressed and anxious to finish a very important conference paper. A friend was being dragged to a concert by his fangirl sister and they had an extra ticket, so I tagged along. I have a predisposition toward boy bands for some so I figured it wouldn’t be a waste of time and I needed something bombastic to distract me. So I found myself at a Big Bang concert. Big Bang is one of the biggest K-pop bands in the world and has settled squarely into legendary status. Suffice to say I left speechless, even though having not been exposed to Korean, I mistakenly thought that they were actually saying nigga in some of the songs. I was very conflicted but that feeling was superseded by my awe at the spectacle, grandeur, and talent. It was such an awe-inspiring experience to witness a mastery of global pop mechanisms in a culturally-specific context, even though it was, essentially, foreign to me. I went home and consumed crazy amounts of Big Bang content. But I quickly switched my fangirl allegiance to a younger boy (technically man) group in Big Bang’s agency and it has firmly remained there since.

With my fandom strongly established I began to watch everything this group, Winner, appeared in, whether it was interviews or variety shows or their own documentaries (they have a 12 episode documentary show in which they open a mini daycare for 10 kids aged 2-6. I’ve watched the full season 5 times). From there I became accustomed to the particular language of Korean variety shows and began to watch shows because I liked them, not just because my favorite idols appeared in them. I also began listening to more music and developed a broader appreciation for the music that falls outside of the K-pop idol machine.

Which brings me back to Show Me the Money. One of the producers is one of the most famous rappers in Korea today, Dok2 (who is actually a quarter Filipino and a quarter Spanish). I watched his Instagram story in terrified, masochistic wonder as he got his hair braided by a Black woman at the Slauson Mall. The Slauson Mall. In South LA. Ten minutes down the street from me. This man had been wearing them way past their expiration date. (Always under a hat because they look terrible and should not be on his head. They look so bad, truly). Why doesn’t his teammate, Korean-American Jay Park, tell him that his braids are offensive appropriation?

This is where I have another fascination with Korean popular music: the way in which members of the Diaspora come home and become superstars. As a first generation American who doesn’t feel like I can truly return to my “motherland," Jamaica, I sit with a strong sense of envy towards those who can. There are of course, unique reasons for that. K-pop is used as a tool of soft power and propaganda; it is subsidized and thus there is a booming market. One only has to look to the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang. Parachutes are sent across the North-South Korea border, with K-pop blasting. Teenagers the world over are learning Korean because they want to watch K-dramas and hear the voices of their favorite idols without subtitles. Asian-Americans are underrepresented in mainstream music. They are Otherized in music in a way that Black Americans are not. Complete aside—We are never thought to also be the child of immigrants. Our assumed history as descendants of American slaves fostered by lazy ignorance of postcolonial migration doesn’t afford us a global and Diasporic identity. Of course, that means we generally escape the scapegoat status that falls to non-Black Latinxs and to a certain extent, APIs, but as a child of a formerly-undocumented immigrant, I have my feelings. But a “return” to a willing nation to realize one’s dreams probably feels like a preferable route to take.

There’s so much more that interests me. Gender. Class. Geography. The history of East Asian colonialism. Direct, personal linkages to Leimert Park in Korean pop music. The role of language. As a Black person, I don’t support fetishizing other cultures. I’m very wary of becoming a card-carrying Koreaboo and take pains to not land in that treacherous territory.

But it’s also painful for me. I live near Koreatown and it’s the nearest neighborhood for me to access some of my ~needs~ as a socially privileged, college-educated Black millennial (cafés with WiFi, non-food desert grocery stores, etc). I’m still unfortunately socialized to make myself non-threatening to non-Black people. On routine trips to Koreatown Galleria for Winner’s new CD, I make myself small. I’m overly polite. I’m defensive. It’s fucked up and I know it. But it’s muscle memory. There is a stinging weight to my enslaved movements and mannerisms as I perform them at stores on Western Avenue, one of the primary locations for the events of the LA Uprisings. Sometimes I think about Latasha Harlins when I walk past the older Korean security guard as I park my bike in the Madong Plaza parking garage.

But I’ll be damned if I let a bit of emotional trauma get in the way of my escapist coping mechanism.

</div>

</div>