The women say that they perceive their bodies in their entirety…

…The women affirm in triumph that all action is overthrow.

—Monique Wittig, Les Guérillères, 1969

A Fan-Zine for Utopia

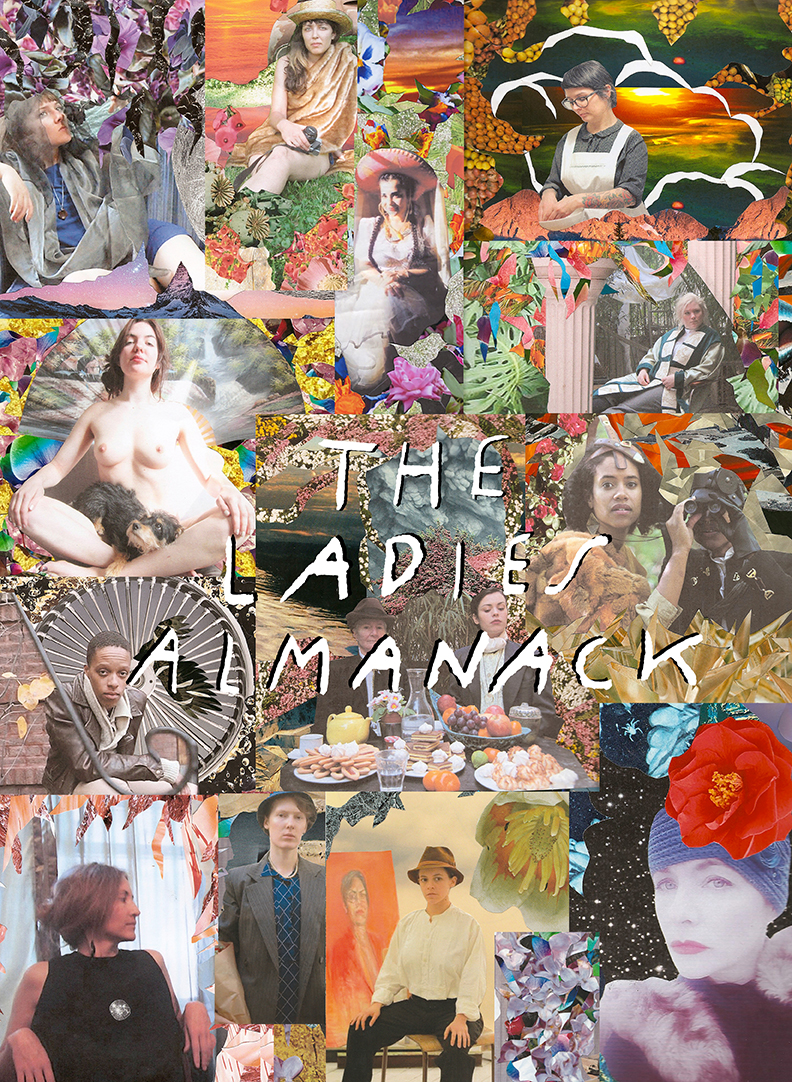

I am a fan of Utopia. I am especially a fan of those who’ve offered a recipe for Utopia. The concepts that ground the philosophy and theory present/ed in my film, The Ladies Almanack, (2017) propose tools for building the future as we want it.

We the living are extensions of the past. Therefore to know who we are we must “always look back.”1

The film looks back to a cadre of artists and writers based in Paris circa 1926-8. Based on a groundbreaking novel by Djuna Barnes, the story focuses on the friends and lovers of the cultural powerhouse, Natalie Clifford Barney.

In The Ladies Almanack the voice of the narrator which is not one2 states by way of introduction:

Monique Wittig: Our story is not comprehensive nor symbolic, but small and hard and real for some. Perhaps for many. Because a lesbian is a real thing, insistent if unpopular. A perspective, specific and narrow. How to speak with a collective, but non-generalized voice?

Hélène Cixous: How to live crying out with frightened joy over the pitfall of words? Fortunately, when someone says woman we still don’t know what that means. Even if we know what we want to mean.3

Luce Irigiray: Who we address, a very special audience, as Barnes herself will come to say, that selective sisterhood is perhaps less necessary to know: for they will know themselves.

To speak of a “we” is always risky. But Utopia demands a community, a “selective sisterhood” that is specific and complex. The first step is defining that community. In The Ladies Almanack and elsewhere, I use the term Lesbian4. Another term I find useful in narrowing the “we” is Radical. Radicals can be defined as individuals aching to be free, who know their liberation is bound up in the liberations of all, and who actively build toward a future that is not like this now. A radical would find truth in Wittig's, “all action is overthrow.” A radical makes Utopia, while others wait.

The Ladies Almanack film is not easy to consume. I chose to make it a difficult watch in part to do the original cryptic Barnes novel justice, but it is also intended to demand a level of literacy from the audiences. From the project’s inception we (myself and producer Stephanie Acosta) determined that our aims in making this work were both educational and utopic. “If this film does not spike the sales of these posthumous authors, maybe even necessitate a reprinting, then we will have failed,” I proclaimed to her in 2014. While we have yet to see if our cinematic fan-zine will impact the literary market, we can re-introduce these writers as a call to radicalize literary education.

Educators of every stripe: stop teaching the canon. Dominant culture has been formed by books they told us to read over others. When Uncle Tom’s Cabin remains on syllabi but Sojourner Truth’s speeches are not, teachers are being lazy and our culture and lives suffer. She who teaches James Joyce without Djuna Barnes should ask herself if she should be teaching at all. Barnes, Joyce and Truth use language toward freedom. But where Barnes and Truth propose utopias, Joyce’s proposed world IS the one we live in today. We are living in the cultural result of the works that have been codified through exposure. What makes a work of literature “important?” Catcher in the Rye, a pseudo-radical book whose popularity has helped to create the world we live in, offers an emotion perhaps rare in its time, but it does not offer tools for a way out. Radical works, such as The Autobiography of Malcolm X, do not become less radical over time.

When I name literacy as one of the main aims of my work, I mean that if you can read, you are responsible to society to read, and you are responsible for what you read. If we are not collecting tools to break down this system then we are actively building it up. Carceral Capitalism, (Semiotext(e), 2018) by Jackie Wang, who plays Lucie Delarue-Madrus in The Ladies Almanack, is the latest example of the literature that belongs in the toolbox on on the reading list of any radical building Utopia today. Thus the fan-fiction of The Ladies Almanack points not only to radicals of the past, but also to minds of the future, to works not yet written, yet part of the legacy nonetheless.

My art (and my life) could be seen as a huge fan-zine to inspirational women of the past and present. Even as I write this, I take breaks to create fan videos of LeCiel playing music and singing. LeCiel is my partner in culture—she plays Janet Flanner and composed the soundtrack and score for The Ladies Almanack. Filming her is an act that occurs as regularly as breathing between us and with as little fanfare. We must sing each other’s praises because it is that song that becomes history.

You for whom I wrote, O beautiful young women!

You alone whom I loved, will you reread my verse…?

-From the tomb of Renée Vivien, poet.

Vivien, who wrote this epitaph to her future fans, was a lover of Natalie Clifford Barney and neighbors with Colette for a period of time. Long dead already by 1926, her character enters the film as a story told, a memory kept. “Would it not be the height of Cowardice to allow our dead to die?” Barney wrote, a quote that floats into the film as one of the inter-titles set between scenes. One of Barney’s most radical contributions was the example of her love life. The entanglements between the women of Barney’s web were not always harmonious, in fact tensions and jealousy outline the perimeters of each character, shading and polishing the emotional bas-relief each woman forms with one another in the film. But non-monogamy is unafraid of these inevitable pricks and cuts. Barney and her friends do get hurt, but they remain sexually free.

In the film, Mimi Franchetti, played by Fannie Sosa, remarks teasingly of Barney’s salon, “I can’t help but wonder what such a mixed crowd could possibly have in common?” Barney replies “Mimi, my friends, they all like when it rains.” Does Barney intend sexual innuendo about female ejaculation or does she imply a depression-welcoming self-loving courage-despite-pain attitude among her circle? Probably both.

The women say that they perceive their bodies in their entirety…

Barney’s relationships have no scheduled “nights off” or rules governing what one lover can do with another. Instead, they abide only by one radical notion: that nobody owns anybody.

In summation, I offer a recipe for Utopia:

1. A self-selecting, specifically defined, intergenerational community that honors complexity, literacy, self-love, and depth.

2. A culture that looks forward and back, aligned with a sense of heritage without nostalgia yet alert to the uniqueness of the present, and armed with the courage required to build something new.

3. Deep professional and emotional commitments to one another that do not shy away from discomfort or pain but rely on the basic rule that nobody owns anybody.

1JT Bruns, Silver Field multiple, “Always Look Back”, 2016.

2 See Luce Irigiray, “The Sex Which is not One,” 1977. In The Ladies Almanack Irigiray, Cixous, and Wittig are cast as the three voices of the narrator, meeting the women of ’28 and those of ’16 halfway in time, an essential if unseen link in the chain.

3 Throughout the film, almost all the words spoken by the voice of Cixous are her own quotes, pulled from various texts in inserted into script.

4For my definition of lesbian, See “No City for A Young Soul” WALLSDIVIDE PRESS, 2016.